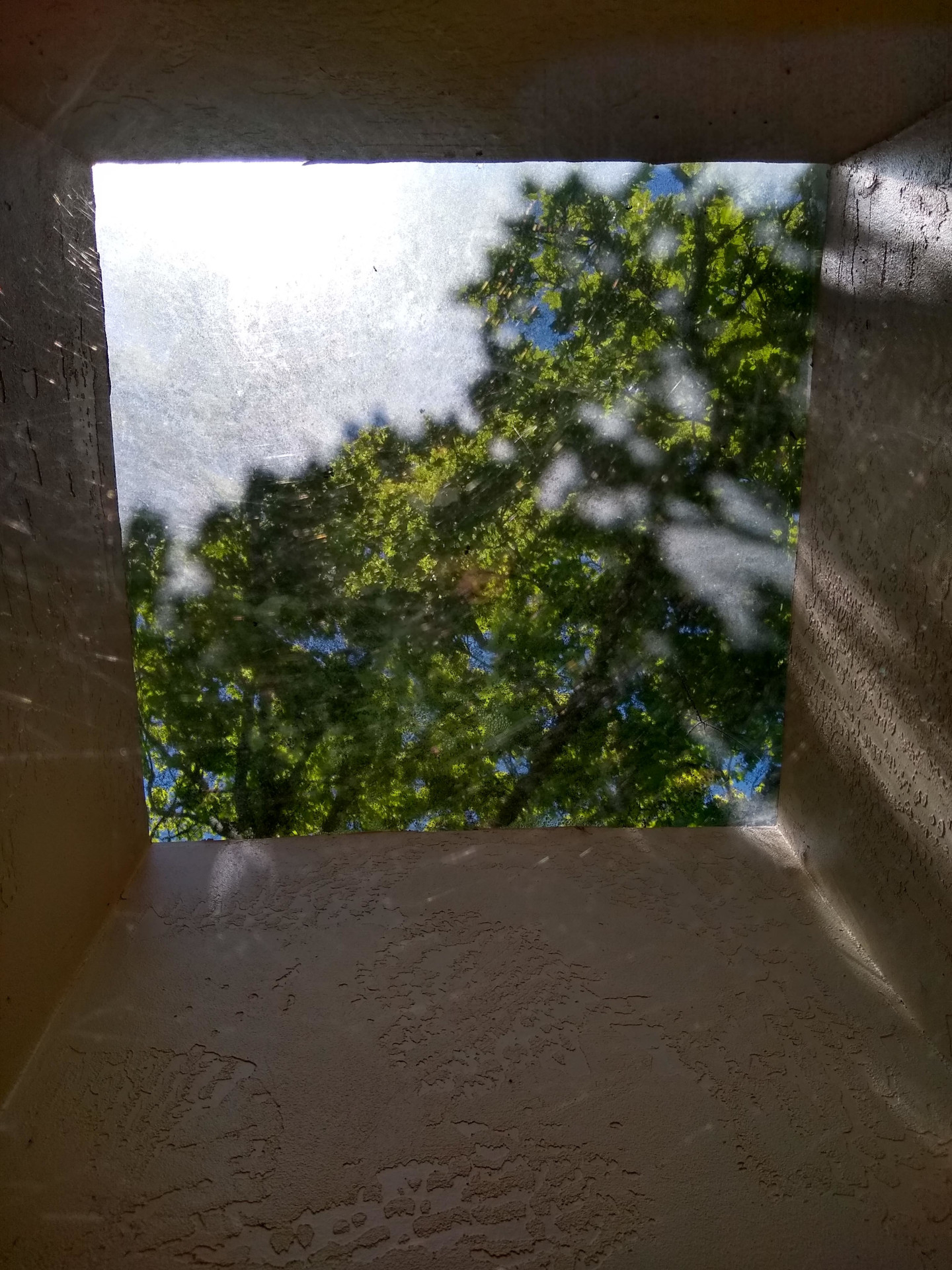

The advertising campaign for the Metropolis–what to call it? “Apartment complex” would be a class lower than the one it intended to target, when it was conceived, before the pandemic–depicted future residents as palimpsests, or more accurately, green screens. Lush flora, tropical birds, clear night skies, skyscrapers, and the Hollywood sign showed through their bodies. “Los Angeles Without Boundaries” read one window-sized poster (the building was all windows), and another, “Your Oasis in the City.”

On Twitter, “you seem fun and smart till you rt a podcaster” was liked by a podcaster.

On the phone, my friend told me she preferred her friend indulge in workaholism than overdose on something else.

I worried about the podcaster whenever I saw her tweets or listened to her podcast. I felt I understood what the aborted denizens of The Metropolis would’ve called her career crisis. Every month or two she announced her commitment to a new plan. She quit her day job (though it was at night) because, she said, it was bad for her mental health. (What work isnt?) She thereafter appeared to be living in her childhood room, self-ouijiing. This was how I imagined my future, despite knowing it couldn’t be like this.

The Metropolis asked “what is Bourgeois time without the Bourgeoisie,” and the question I held back asking my friend about her friend was: What is addiction but a work of art that its subject, work, interrupts?

An oasis without boundaries is not a contradiction. The couple I was housesitting for told me that the rural isolation they esaped to was just like the isolation they hadn’t known they had already felt in the city.

We all had been noticing that the piling up of epistemic upheavals made relatively recent memories feel very long ago. Performing noticing became addicting. It was so long ago when someone at work said “good morning” to me and I said “wasn’t I just here?” A theatrical excess to demonstrate what I felt.

The company that owned the company I worked for rented the adjacent warehouse space. I assumed this was how they had spent their pandemic relief grant. It was referred to as “the market,” and was connected to the bakery through a door at the very back, at the end of the hallway where the bathrooms were. It opened, from the perspective of the bakery, to the break room. Sometimes I would go past the break room into a room filled sparsely with shelves of dry goods, to look for cleaning supplies, and I never saw anyone. The shelves were preposterously lower than the ceiling. The lights were always off, and I would search the supply closet with my phone’s flashlight. People that eventually I understood worked on that side sometimes appeared in the bakery, to use the computers in the office, or to clock out. Sometimes, who I took to be the boss on that side would tell me to change an order, a change that the boss on the next shift would ignore. The boss who trained me said that the space next door was a “distrubtion center,” which he elaborated was “a new business model idea,” before disappearing in a huff through the swinging doors.

On my days off I restlessly awaited dusk, when I could finally go outside. I walked up the same trail in Griffith Park. The last stretch before turning back I thought of as the best part: where the repurposed road, with its crumbling asphault, flattened out and hugged a cliff. That wall on one side, the result of blasting the road in, made the walk cozy, and the view on the other side was of Glendale, which mercifully lacked the iconicity of downtown, the observatory, or Hollywood. The hikers on the trail along the ridge at the top of the cliff were on their way to Mount Hollywood in the last of the sunlight, and, observing them from below, my pace slowed. They seemed to teeter.

I don’t know if the internet finds you or you find the internet, but the homing instinct is extrmely long-ranged either way. Over time, internet crushes become repertoires of externalization. Perhaps a crush is an identification mistake. Years after the initial crush, she appears to be living a life you could have led.

On Instagram, as I was told via Whatsapp, an internet crush was coming out sneakily, without fanfare. Not that there was any need to pretend a break had occured. But I knew she only achieved un-self-consciousness through great self-consciousness. This, along with all male knowledge, was suspect. Her life as I knew it flashed before my eyes. Was it all internet irony, my friend wondered? I recalled what she had said on a chat podcast: Why come out at all? Ideally, she had said, nobody should come out, or everyone should come out. At another time, she had said that she wasn’t in the subject position to say so herself, but if a lesbian recommended everyone become a lesbian, she would’ve agreed. My friend and I became interested in her husband for perhaps the first time. In an article he wrote, not precisely about her, but about the general case of marriage to a woman, he lifted a phrase from something she had written a few years before. At first, I didn’t think this was a copy-and-paste, but aesthetic mimicry. It almost sounded to me like something she would write because I imagined that would be what I would try to do, if I were in his position. I wouldn’t want to be in a relationship with me.

By this time, “pilled” as a suffix had multiplied to the point that anything could be a pill, even a grill. Podcasters routinely apologized for potentially blackpilling their listeners, or for talking while blackpilled, or in other words, having become a nihilist for two minutes on air. “Pilled” had become shorthand for the way that perception could change abruptly and completely. Meanwhile, a musician released an album that she worked on during the pandemic, on which she listed all of the pills that she wished would allow her to sleep. Pills were there to quell the results of being pilled.

It’s said that everything depends upon first impressions. On my way to work one day, two exhibitionist-yellow cars, one behind the other, turned left and passed in front of me as I waited at an intersection.

At work, dough dropped through the baguette shaper, called a “Unic,” and was impinged between two rollers. Bits of the dough got stuck on unseen parts of the rollers, and came out the next day embedded in the rolled baguettes–hard, yellow chunks that felt satisfying to remove, like scabs.

On the reincarnation of IRC twenty years later, Lilith and Eve were being discussed. “Where did Lilith come from? The idea of her, I mean.” In answer, someone posted a link that stated “in the midrashic account, Adam is the most beautiful creature,” Eve being the most beautiful after him, and God of course being more beautiful than Adam, but not a creature.

The plaque on the Pioneer probe depicts a man and a woman, both devoid of pubic hair, and the woman lacking a vulva.

“Sardonic” is alleged to derive from the ancient Greek belief that, to quote the Online Etymology Dictionary, “eating a certain plant they called sardonion (literally ‘plant from Sardinia,’) caused facial convulsions resembling those of sardonic laughter, usually followed by death.”

At work, the lead croissant baker came in just after I had scored the loaves.

“I like slashing them,” she said.

“Something that can’t be undone,” I said, smiling.

“I miss it,” she said.