In a badly written piece of praise for a walled garden in a city my friend feels is less bearable than the city she lives in, that the same friend wants to visit during a two-day trip-within-my-trip that I won’t tell anyone I know in the city about, there’s a passage from The Secret Garden:

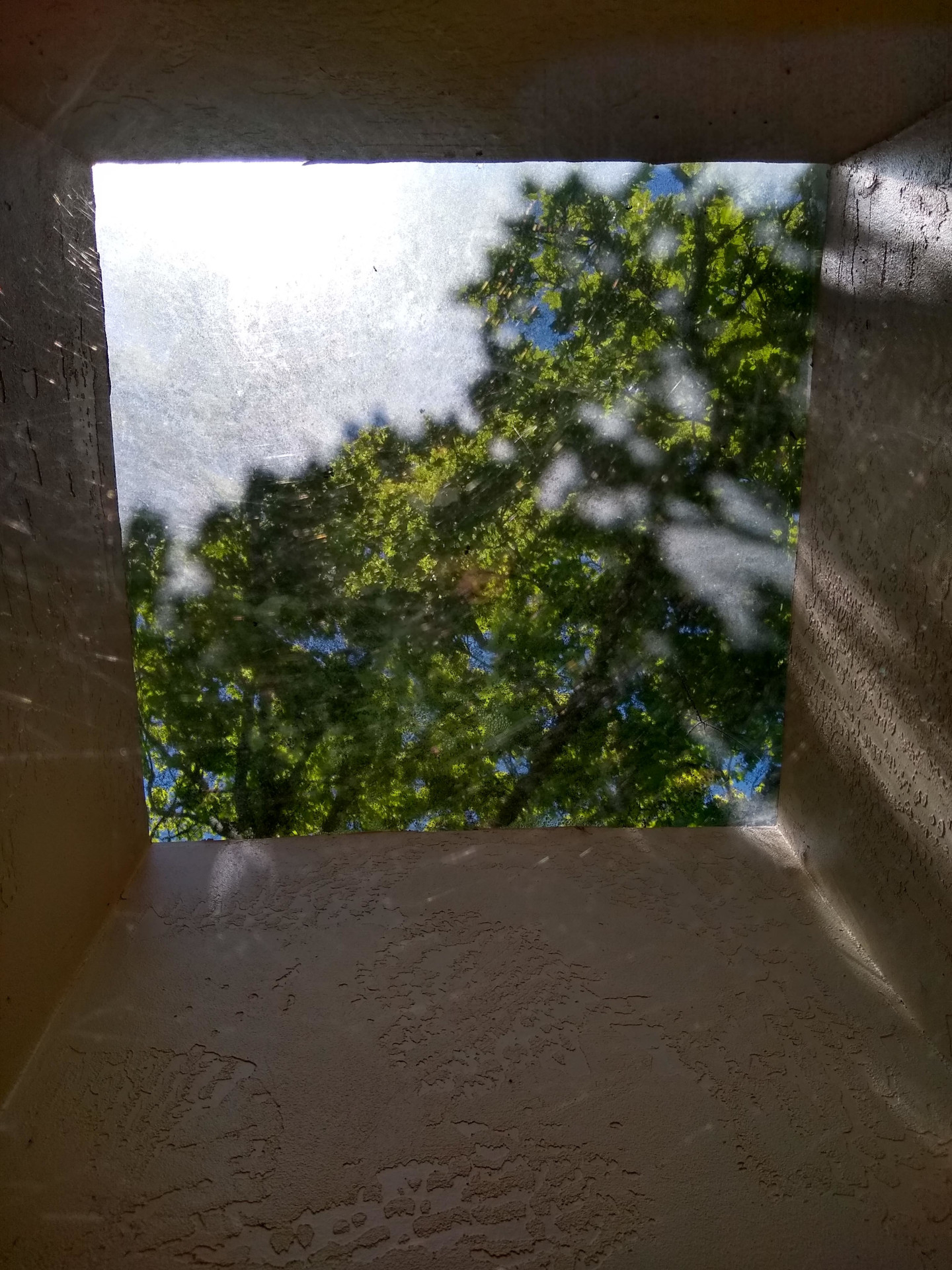

Sometimes since I’ve been in the garden I’ve looked up through the trees at the sky and I have had a strange feeling of being happy as if something was pushing and drawing in my chest and making me breathe fast.

This is a feeling that I either feel nobody can get from looking at trees, or feel bad that I can’t feel by looking at trees, or indeed by looking at anything. Ever since a moment I can’t put my finger on, can’t touch, anything I look at has become Cartesian–like a map (if you’ll excuse the pun). I look at someone, and with a violence that surprises me, I say aloud “I can’t tell what you’re thinking.” When I looked at same as a contact on my phone, and hovered my thumb over the call button, I didn’t feel slow CPR on my chest, but a threat. I thought about intentionally delaying hitting the call button for as long as possible, because fear felt like pleasure, but I had to believe, in good faith, that I really would call, to feel afraid of calling.

The leaves are bursting from the trees, the air is warm, the birds are trying to fuck, the bees are swarming the flowers, I hate the trees, I hate the birds, I hate the bees, I hate the flowers, I hate seeing. I’m in the hot wind of an air popper, and everything is suddenly becoming something else. I read one essay by a Zen Buddhist and think I understand the concept of joy, which I feel is a sheet of paper, even though I know this is wrong. “Joy is exactly what’s happening, minus our opinion of it.” I’m afraid of a lack of opinion, I feel opinion is the third dimension.

A map is a plan for possession, and I make pins out of how I feel I’ve wronged. I think that how I’ve wronged a person is keeping that person from me, but I suspect that without feeling I’ve wronged, I would feel untethered, which strikes me as very Abrahamic. I imagine all of my apologies, each one describing, I think, the precise way I’ve wronged (but I rephrase them every time I repeat them). I imagine the scene in which I apologize, stopping conveniently short of how the recipient would respond. If I were an insect in the garden, and I were caught in a net, how long would the moment of the pin pressing against my exoskeleton seem to last?

Through a garden gate, through a door, in frames on the wall are photographs of Nature–a black volcano softened by layers of haze over a green valley, a waterfall with dogwoods cascading over its precipice in parallel with the water, a shadowy redwood forest, with thick canopy and thick duff. All carefully composed to cut out any evidence of the people, the photographic apparatus, the road, the power lines, recent forest management. The owners of the photographs tell me that what’s amazing about the city where my garden-seeking friend lives is that there’s a lot of wildlife. In the middle of the city you’ll meet a coyote, a hawk, a rabbit. I picture these pictured within yellow squares of facial recognition.

The itinerary my friend is planning for the two days we’ll be in the city form a certain slice–ballet, afternoon tea, French restaurant. Between these we’ll walk over the layers of falling apart and restoration, waste and removal.

Exit is only moral if vertical, like pushing and drawing on the chest, which is presenting itself upward. Leave horizontally and you’ve forfeited something. A house for Gaston Bachelard is “oneirically incomplete” if it is composed of “mere horizontality.” Moreover, city dwellers’ apartments lack “cosmicity”: you can’t lay down in a garden and look up at the sky. If this were a certain kind of essay, I would say something here that would boil down to “horizontality is revolutionary praxis,” which would be to rhetorically rearrange horizontal into horizon. In a recent video, FKA Twigs dances up an infinite pole toward a gauzy heaven only to descend into a shallow pit of mud, mud that the pit’s inhabitants coat her in, forming a barrier with which she will experience the world anew or will preserve her former experience, like skin but not skin.

Surrounded by unreconstructed Atheists, my position–boring to many but incomprehensible to the Athiests–has become that the religion they claim to have exited remains as an unacknowledged text of secular activity. Brought up by a recovering Catholic father and an Agnostic Protestant mother, I’m religiocurious, which makes the texts I impute to various secular institutions and thoughts often hilarious, like looking in my father’s messy storage sheds when the light bulbs are broken. Unlike the Freudian uncanny, it’s not necessary (even secretly) to believe in that which modernity left behind to be haunted by everything it has never left behind.

All my mother’s horizontal escapes–to other dwellings, other cities, other men–were, in the logic of the garden, what she had to pay for with descents into maritally-supported depression and one ascent to a mountain from which she escaped the only way that’s complete.