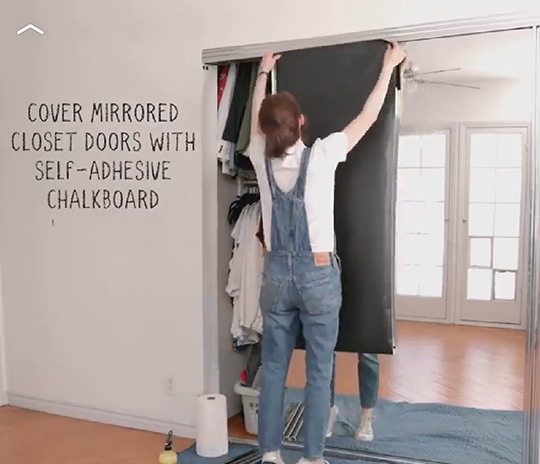

On Instagram I saw an ad for I don’t know what that showed a woman in coveralls covering a mirror sliding door with an adhesive sheet of chalkboard. “Smooth out the bubbles from the top down,” advised the ad, and it looked like she was installing an opaque, black screen protector on a phone the size of herself. I found myself wondering what a person like the one in the ad would write or draw on the chalkboard. I once knew a family who had a chalkboard in their kitchen, and it was full of each member of the family’s promises to the family, binding them to their optimisms. There were elements of life plans as well as weekly chore schedules. As a member of a family who never trained any of our dogs, I felt like Elizabeth Jennings looking at paintings.

I no longer know this family because of my family, but I never really wanted to know them. A falling out in a work relationship that was more than a work relationship (like every work relationship) has been redacted, so that this isn’t something I should be talking about, except that nobody who would care will ever read this. Through this game of chicken between straight men, there appeared to be two sides, and on the other side was this family.

Before all this, I housesat for them once, and with them gone, the curiosity I had about their lives mostly evaporated. But going from visiting a place to living in a place only means going from eavesdropping on to overhearing objects. The spines of her books staring at me as I lay in their bed, I found myself helplessly speculating about the life of the house’s matriarch. I quote my speculation here, as if I haven’t written it concurrently:

A punk with a lot of younger friends, she enchants her family life with her Midwestern engineer husband by being involved in the radicalism of twentysomethings. She uses her and her husband’s money to fund nonprofits and direct actions, and the activists like to hang around the aura of newslessness of the bourgeois family, like moths. She in turn goes to rallies and meetings, where she’s embroiled in controversy, which is what the restful, abyssally perfect forms of her husband’s MIT education lack.

Her two children are a kind of reproduction of mother and father–she highly socialized, witty, star of high school theater, and applying to drama schools, he quiet, serious, and an aspiring writer. These aspirations are taken very seriously, put up on the chalkboard. On the chalkboard, they’ve had Passions and Paths since adolescence. One time we all took a hike in the snow on a foggy day, and the son got far enough ahead of us that we couldn’t see him anymore. His mother said with an wistful, annoyed laugh that “he’s always been a child of the fog.”

In other words, I couldn’t (read can’t) imagine her life without thinking of her husband as the opposite of a mirror, because that’s what my devotion to my childhood friend, who smoothly went from aeronautical dreams passed down from his North Dakotan grandfather to studying engineering at MIT, felt like.

In Arrival, it becomes apparent that Amy Adams’ character has been more or less writing on a whiteboard to her not-yet-conceived daughter this whole time, not to the aliens in the fog behind the screen of the cleanest movie theater of all time, but a pre-pre-fetus who appears as intrusive visions a.k.a. memories that feel like a loss or a post-apocalypse, but turn out to be the bright future of humanity. After all, she wrote “HUMAN” on the whiteboard, like the first item on her wish list to Santa.

I think I never want to intend a thought again, like a drug addict, but on the other hand I’ve become addicted to writing about (or over) my self-regard. Posting what feel like heinous acts of self-presentation brings a cycle of shame, during which I consider all the ugly implications of what I’ve written, and imagine, unbidden, the thoughts of the three or four people who might read it. It’s clear that embarrassment is addictive, and it’s unclear whether embarrassments are additive. Do I yell at myself about things I’ve written on the internet instead of yelling at myself about things I’ve said in person, or do I just yell at myself more?

Last month I tried to write an essay for a magazine, which was embarrassing. The essay repeated itself and meandered, at once anxious to tie everything to a thesis, like academic writing, and full of nonsequitors. The essay was supposed to be about how a particular director liked to sidestep the embarrassments of his youth by very subtly making fun of them. Writing scripts that hewed close to his life, his authorial voice, my argument went, became the way he wanted to be regarded by someone else.

Obviously I was projecting, but then again what I thought the director was trying to do–to sneakily become graceful–was exactly what I haven’t been doing. I decided that the director had come to the conclusion you can’t convince anyone, you can only make them laugh.

Alan Turing’s paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” seems peculiarly disinterested in convincing its reader. Its argumentation is all in the negative, listing every argument he can conceive against the validity of the method he proposes for answering the question “can machines think?”, a question he introduces and then throws out. He insists that the test he proposes to answer it–in which a machine attempts to convince a human “interrogator” via text messages that it’s a woman, and that a human woman, also texting the interrogator, is not–does not answer that question, but another one. He proceeds to take up this “imitation game” as his stated rhetorical mode: “These last two paragraphs do not claim to be convincing arguments. They should rather be described as ‘recitations tending to produce belief.’”

In the middle of this more performative than argumentative essay, he considers the problem that telepathy poses to the validity of the imitation game, which requires that the three participants be in separate rooms, and decides that the solution is quotation marks: “The situation could be regarded as analogous to that which would occur if the interrogator were talking to himself and one of the competitors was listening with his ear to the wall. To put the competitors into a ‘telepathy-proof room’ would satisfy all requirements.” This seems like the game’s most serious hang-up. Where to find a room that doesn’t speak? Or a thing that doesn’t think?